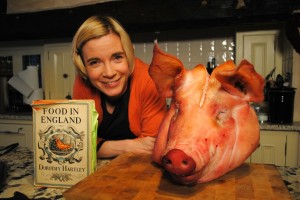

New BBC film: ‘Food in England, The Lost World of Dorothy Hartley’

‘‘Food in England’, The Lost World of Dorothy Hartley’

… is a brand-new programme due to be shown on BBC4 at 9pm on Tuesday 6th November.

It’ll be accompanied by a new edition of some of Dorothy’s journalism from the 1930s, ‘Lost World’ (left), published by Prospect Books with an extensive new biographical introduction. Any journalists interested in the book or film should please get straight in touch.

The programme tells the story of the woman behind the ultimate book on the history of cooking, ‘Food in England’ (Macdonald, 1954).

Published in 1954, the 600-page ‘Food in England’ took Dorothy Hartley 30 years to write. I’ve had a copy on my bookcase at Hampton Court for years, because it’s a treasure trove of odd facts and recipes.

Published in 1954, the 600-page ‘Food in England’ took Dorothy Hartley 30 years to write. I’ve had a copy on my bookcase at Hampton Court for years, because it’s a treasure trove of odd facts and recipes.

It’s a curious mixture of cookery, history, anthropology, folklore and even magic, illustrated with Dorothy’s own strong, detailed and lively illustrations. It ranges from Saxon cooking to the Industrial Revolution, with chapters on everything from seaweed to salt.

And it certainly isn’t a conventional history book. I must admit that I’d previously had some reservations about it because it doesn’t have proper references to source material, or footnotes. Infuriatingly, Dorothy breaks the first rule of the historian: to cite evidence.

Despite this, I’d always been a big fan of ‘Food in England’ for its readability and exuberance. Until a year ago, though, I didn’t know much about the woman who wrote it.

Despite this, I’d always been a big fan of ‘Food in England’ for its readability and exuberance. Until a year ago, though, I didn’t know much about the woman who wrote it.

Over the last twelve months, David Parker and his TV company Available Light and I have been filming the places Dorothy lived and the people she knew, for BBC4. We went up and down to the country, visiting the various houses she called home, following her through the seasons of the year and along the journey of her life, and recreating some her weird recipes, from brawn to quince jelly to the ‘medieval pressure cooker’, a barge-man’s dinner cooked in a bucket.

As we travelled, I began to realize that my frustration in her technique as historian was misplaced.

The book ‘Food in England’ was really born in the 1930s when Dorothy had a weekly column in ‘The Daily Sketch’ newspaper. To write it, she too travelled about, by car or bicycle, sometimes sleeping rough in the hedge, and she talked to old ladies and gentlemen of the countryside who were still just about doing things the old unchanging way, just before mass production and mechanization and industrialisation.

The book ‘Food in England’ was really born in the 1930s when Dorothy had a weekly column in ‘The Daily Sketch’ newspaper. To write it, she too travelled about, by car or bicycle, sometimes sleeping rough in the hedge, and she talked to old ladies and gentlemen of the countryside who were still just about doing things the old unchanging way, just before mass production and mechanization and industrialisation.

In this sense, it’s a work of oral history, as Dorothy was talking to the last generation to have had countryside lives sharing something in common with her great hero, the Tudor agricultural writer Thomas Tusser.

Dorothy was born in Skipton in Yorkshire in 1893 at the boys’ grammar school. Her father was its headmaster, and her mother head of catering for sixty boys. We had one fun day with today’s pupils trying to cook recipes like ‘Stargazey Pie’. (Herrings in a pie – with their heads left on and sticking out round the edge.) Little Dorothy would visit the farmhouses of the Yorkshire dales to see sheep sheared, oatcakes baked and scoff huge Yorkshire teas. As her father’s eyesight failed, the family moved to the rectory of Rempstone on the border of Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire, the area in which I spent my own teenage years. As well as visiting the rambly old house with its garden full of fruit where the adolescent Dorothy first began writing and drawing, we visited a restaurant run by an old schoolmate of mine who restricts himself to ingredients from within a twenty mile radius, just as the Tudors did.

With Dorothy’s biographer, Adrian Bailey, I examined letters from a few years she spent travelling in Africa, and learned the tantalizing story of her great lost love, the heavy-drinking bush ranger whom she later said she should have married.

One of Dorothy’s early projects was a new edition of Thomas Tusser’s immense poem about sixteenth century farming, and down on the border of Essex and Suffolk I visited the remains of his house, and had a go at ploughing for myself with gigantic Suffolk punch horses.

Then we began skipping about all over the place, just like Dorothy herself in her role as the roving reporter for rural England in the 1930s. At this point I began to realize that not only was she a terrific oral historian and journalist, but a pretty unusual woman for her time. Far from settling down, she speeded up, refusing to marry or have children and indeed devoting herself entirely to her work of recording the past.

Finally ‘Food in England’ came to fruition in the home she inherited from her mother in the Welsh village of Fron, outside Llangollen. Here, in 1954, now in her sixties, she published her magnum opus. People instantly recognized its value, and it has never been out of print since.

Dorothy only died in 1985, and some of her friends are still alive and well. Together we had a poke into Dorothy’s handbag, and found within it a very characteristic collection of objects: a ticket to the reading room of the British Museum, a penknife and an atlas. She was certainly a woman who knew where she was going.

I was really struck how much Dorothy’s friends still seem to miss her, and the nature of their memories. In some ways she was decidedly odd. They describe her as abrupt, impatient, wrapped up in her study of the past. Apparently, if she was busy, she’d answer the phone with ‘Go away, I’m in the fourteenth century’. But despite that, and despite a constant shortage of ready cash, she was generous as the sun. Dorothy’s friends clearly regret the fact that she left no children, but I relish the fact that she did instead leave us this amazing book.

It was only as I followed Dorothy up and down the country from Yorkshire, to Leicestershire, to Suffolk, to Wales, that I came to appreciate how magnificently eccentric she was. She really did devote her whole life to this completely mad quest of capturing a lost world. And thank goodness she did, because the world needs crazy, passionate people like Dorothy.

It was only as I followed Dorothy up and down the country from Yorkshire, to Leicestershire, to Suffolk, to Wales, that I came to appreciate how magnificently eccentric she was. She really did devote her whole life to this completely mad quest of capturing a lost world. And thank goodness she did, because the world needs crazy, passionate people like Dorothy.

The final image of what I hope is a warm and celebratory film is a home movie of her in old age, showing her doing what she loved to do: working in the garden, and digging up potatoes for dinner.

Hello Lucy, my husband and I have discovered your documentaries on YouTube! You are absolutely a delight! We love the historical stories that you tell. Well done! Where can I get a 1954 copy of Food In England? Thank you, Debra Jenner-Billington

Just wondering if your programme on Dorothy Hartley is likely to be screened in the near future. I would to know more about her.