Jolly Good Fun: Parlour Games of the Past

The long hours of New Year’s Eve stretch ahead of you next week … do you need some ideas for entertaining your family and friends? If so, check out my article from January’s Period Living magazine! I think that the magazine itself is just about still on sale, and I can tell you, having a copy of my own, that it features some houses to induce a visit from the green-eyed monster.

The long hours of New Year’s Eve stretch ahead of you next week … do you need some ideas for entertaining your family and friends? If so, check out my article from January’s Period Living magazine! I think that the magazine itself is just about still on sale, and I can tell you, having a copy of my own, that it features some houses to induce a visit from the green-eyed monster.

‘Imagine a long winter evening stretching ahead of you – in a world without electricity.

It would cost you a lot of money to burn a candle, or turn on the oil or gas lamp. And even if you did, you’d scarcely be able to see to read in the dim and flickering light. How on earth are you and your family to entertain yourselves for the hours to come?

No need to panic. Around the open fires of homes throughout history existed a whole lost slice of life: DIY home entertainment, or the parlour game.

An indoor game for groups is as old as history. For example, Henry VIII’s courtiers were enthusiasts for covering their eyes and chasing each other in a game of ‘Blind Man’s Buff’ (a ‘buff’ is a ‘little push’). They also likedgambling on dice or card games to pass the empty hours. Francis Willughby’sBook of Games from the late 1600s describes the rules of backgammon, and gives instructions for card games that begin with the very manufacture of the cards themselves: take ‘3 or 4 pieces of white paper pasted together and made very smooth that they may easily slip from one another, and be dealt & played’.

But enjoying oneself was not the top priority in the hierarchical days of the Tudors or the Stuarts. The most important person in a room would sit in solitary splendour in the best chair, showing off his or her rich clothes, while everyone else stood and watched and admired. In the Georgian age, however, aristocrats grew bored with the stiff rituals of their caste. One character in a Georgian novel complained that ‘all the ladies sitting in a formal circle’ had nothing to say to each other, and she herself was ‘like a bird in a circle of chalk that dare not move to much as its head or its eyes’.

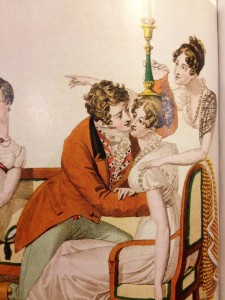

And so a new informality entered fashionable life, and there was a metaphorical loosening of the stays. In Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (1814) the young people amuse themselves by performing theatricals, although this displeases the story’s heroine, who gets horribly jealous when her own preferred young man has to perform a love scene with another girl.

The object of a parlour game like ‘Hunt the Slipper’ or ‘Blind Man’s Buff’ is often to come into intimate contact with your friends, or perhaps your paramour, and you might be surprised by the amount of kissing involved in Victorian amusements. Sometimes the loser of a game would have to perform a forfeit, such as to ‘Kiss The Lady You Love Without Anyone Knowing It’. In this case, the well-informed Victorian gent would kiss all the ladies in the room, and the secret of his preferred lady would be kept safe.

The writers of Round Games for All Parties (1854) found that ‘great objections exist to the introduction of ‘kissing’ in games’, and righteously announced that the games in this particular compendium were only ‘to be played exclusively in family parties, consisting of brothers, sisters, maiden aunts, grandmothers and uncles’. One should think twice, we’re told, before allowing the introduction of even a cousin into a kissing game.

Some games could be quite rowdy, and even dangerous: the Christmas game of ‘snapdragon’, for example, involved putting raisins into a basin of brandy, igniting it, and them plucking the burning fruit from out of the blue flames. ‘The spirit is set of fire’, in a darkened room, we hear in 1811, ‘and the company scramble for the raisins’.

Queen Victoria herself preferred more sedate and sedentary pastimes. Still, her journals frequently contain phrases like ‘after dinner we played at games, and laughed a good deal’. She often enjoyed draughts, a ‘game of letters’, and a rather mysterious ‘game of German Tactics’. Her clever husband Prince Albert constantly thrashed her at chess.

As the nineteenth century progresses, we hear of some very silly games indeed: like the ‘Laughing Chorus’ described in the Young Ladies’ Treasure Book (1880). To be played ‘round a good fire in the long winter evenings’, ‘the person in the corner by the fire says, “Ha!” and the one next to him repeats, “Ha!” and so on … no one who has not played this game can realize its mirth-provoking capacities’.

A higher-minded form of entertainment was to be found in riddles and rhymes. Back in the seventeenth-century, Francis Willughby pays homage to a quick-witted friend of his, who was challenged to come up with a rhyme for ‘porringer’. Today these shallow dishes with handles are often given as a christening present, but originally they were used for slurping up milk or gruel. The poet had remembered that Princess Mary had recently been married to William of Orange. So he said ‘The King had a Daughter & he gave the Prince of Orange her’.

Francis Willughby was kind of early sociologist, capturing the habits of his contemporaries in his unpublished Book of Games, as if it were an academic treatise. By the nineteenth century, though, you could choose from a huge range of commercially available printed books of parlour games.

As the Industrial Revolution progressed, manufacturers became willing to sell you fireside entertainment in other forms too. One of the earliest mass-produced board games was ‘The Mansion of Happiness’ (1800), a kind of snakes-and-ladders printed on linen, which also encouraged children to be good Christians. The message had become less specifically Christian in compendiums from the 1930s such as the ‘Baffle Book’, but it was still moral. It was a series of puzzles for a family to work out together, often solving crimes, with right trumping wrong and order vanquishing disorder.

The Christmas stalwart of ‘Cluedo’ wasn’t invented until 1949, but it had its forerunners in the rather more adult-orientated ‘Murder Dossiers’ of the 1930s. These contained reproduction crime scene photographs, testimony from witnesses, and clues such as hair, burnt matches and even a scrap of bloodied curtain. You were supposed to read all the information, come to your own conclusion, and only then open the envelope at the back containing the solution to the crime.

Today parlour games are largely reserved for family Christmases or special holiday gatherings. What caused their decline? As F.R.S. Yorke explained, even back in 1937, ‘the amount of time in the home has in recent years been much reduced through innovations such as the cinema, cheap travel, careers for women, crèches and so on’. For those who still spent the occasional evening at home, the radio provided a new focus for the living room.

But even when TV came along to challenge radio, we find an old art taking on a new form. A game show like Only Connect or University Challenge is nothing more than a grand and glitzy form of parlour game.’

Lucy, thank you for giving this – as usual – interesting and fun article: you really do brighten up the darkest day with your elegant and also witty prose.

Hoping you have a really super 2014.

Thank you, and to you!

“German Tactics” was a game involving marbles on a board.

In 1742 Edmond Hoyle published his “Book of Games”, which remains available as the definitive guide to the rules of a great number of parlour games. An entertainment in itself.

ymgw.blogspot

Dear Lucy, I truly love all the work you’ve done

thoughtful as well as wonderful., if I may be so bold

and ask where you purchase your wonderful wool coats & sweaters, I have shopped online at Harrods

but no luck. Gratefully.

Nora from USA

Dear Nora, I often get them from Brora. Expensive, but they last forever. Best wishes, Lucy

Very gratefully yours.

Sincerely,

Nora

Hello, I log on to your blogs like every week. Your writing style is

witty, keep doing what you’re doing!