Why I love Dorothy L. Sayers

The final episode of ‘A Very British Murder’ will be on the goggle box again on Saturday 17th January at 8pm, and it includes my absolute tip-top favourite detective novelist, Dorothy L. Sayers. I really wanted to make the entire programme about her, but they wouldn’t let me! So, for my fellow enthusiasts, here’s the chapter from my book about murder which tries to explain why I love and admire her. What a woman!

‘What would those women say to her, to Harriet Vane, who had taken her First in English and gone to London to write mystery fiction, to live with a man who was not married to her?’

‘What would those women say to her, to Harriet Vane, who had taken her First in English and gone to London to write mystery fiction, to live with a man who was not married to her?’

Thus Sayers introduces her character Harriet Vane (or perhaps herself) in Gaudy Night (1935).

At first sight, Dorothy L. Sayers (1893−1957) looks indomitable: full of certainty, self-confidence and strong opinions. A born newspaper columnist, she seemed to hold trenchant views on nearly every subject under the sun. But above all, her passion was for clarity of language and thought. She concluded her (often damning) reviews of other crime writers for the Sunday Times with a section of her column called ‘The Week’s Worst English’, and described the abuse of grammar as ‘treason’.

Ngaio Marsh described Sayers as ‘robust, round and rubicund’, a cross ‘between a guardsman and a female don with a jolly face (garnished with pince-nez), short grey curls, & a gruff voice’. Sayers herself claimed that her life was ‘far too humdrum to be worth writing about’. And yet this was far from true, and smacks of deflection. She was a woman far more complex than her projected public image as busy, even bossy, figure, organizing a club for her fellow fiction writers and directing the future of the Church of England.

Given the circumstances in which she was born, Sayers played her hand boldly and bravely. From today’s vantage point, her life seems crowded and rich with friends and incidents and projects, and yet at the same time painfully lacking in love. She used her gregariousness, and her pen, to create substitutes for the husband and children she would dearly love to have had. It seems impertinent to feel sorry for someone so impressive in so many ways, and yet she left enough of a record of her inner thoughts to show that in some ways she would have liked a life that was more conventional.

Physically, Sayers had strong features and a heavy body; mentally, she was combative and steely. And life did nothing to soften her edges. Her father was in the Church, and she was brought up in the bracing atmosphere of a vicarage. In 1893, when his only child was born, Henry Sayers was a chaplain at Christ Church Cathedral in Oxford, but the family soon moved to the small village of Bluntisham-cum-Earith in Huntingdonshire. It sounds like a made-up place from a detective novel, and indeed Dorothy L. Sayers would turn it into one, in The Nine Tailors (1934), many peoples’ favourite among her novels, with its plot revolving around the intricacies and eccentricities of bell-ringing and bell-ringers.

After rather a lonely Fenland childhood, Dorothy found fun and friends at Somerville College, Oxford. Here she made lifelong connections − ‘The Mutual Admiration Society’ − sang in the Bach choir, flirted with unsuitable men and was truly happy. The nostalgic tone of Gaudy Night (1935), her finest novel, set in an Oxford college, suggests that this was the only period of her life of which this could be said.

Sayers earned herself the equivalent of a first-class degree, but it was not until 1920, five years later, that women were allowed to become full members of the university. The precariousness of the position of the women of Somerville College, tolerated rather than welcomed by their male peers, is another theme of Gaudy Night. A note from Sayers’ tutor warns her against being ‘smart’: it was not a quality then required or even desired in a female.

Her first works in print were poetry produced in the few years following her degree. Lacking the strength to tear herself away from the scenes of her undergraduate bliss, she found a job with the publisher Blackwells, and published some rather terrible verses about her favourite town:

‘Oxford! Suffer it once again that another should do thee wrong / I also, I above all, should set thee into song.’

Her career as a junior editor was short-lived − her boss called her ‘a race-horse harnessed to a cart’ − and Sayers knew that she wanted to write for a living. She moved to London in search of work. This was a low period, during which she often feared that she would have to give up and find permanent paid employment as a teacher. She was genuinely hard up and short of money for food.

At the eleventh hour, in terms of her finances, Sayers found a job she seemed born to do, and it involved writing of a sort. She became a copywriter at Benson’s, an advertising agency in Holborn. Living in a Bloomsbury flat and walking to work in the busy office, Dorothy’s life became almost a 1920s version of Mad Men. She felt at home among the male copywriters, who valued her sharp brain and gift for words. The noisy, competitive, jokey atmosphere of the advertising agency would be lovingly recreated, years later, in Murder Must Advertise (1933). Its plot is preposterous, but what every reader remembers is its vivid picture of office life between the wars. At Benson’s, Sayers created memorable campaigns such as ‘The Mustard Club’ and a celebrated jingle for Guinness involving a toucan:

‘If he can say as you can / Guinness is good for you / How grand to be a Toucan / Just think what Toucan do.’

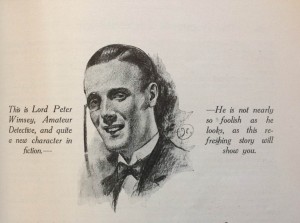

Finally, in her thirtieth year, she sold the detective novel upon which she had been working in her spare time. Whose Body? (1923) introduced Lord Peter Wimsey, the man who would lead Sayers out of her wilderness years and into financial security, and a career as a full-time novelist.

Lord Peter Wimsey saw Sayers through these difficult times. He was a financial – and, one suspects, an emotional − support to her. For a start, she took great pleasure in spending his money. ‘After all, it cost me nothing,’ she later explained,

Lord Peter Wimsey saw Sayers through these difficult times. He was a financial – and, one suspects, an emotional − support to her. For a start, she took great pleasure in spending his money. ‘After all, it cost me nothing,’ she later explained,

and at that time I was particularly hard up … when I was dissatisfied with my single unfurnished room, I took a luxurious flat for him in Piccadilly. When my cheap rug got a hole in it, I ordered an Aubusson carpet. When I had no money to pay my bus fare, I presented him with a Daimler double-six, upholstered in a style of sober magnificence, and when I felt dull I let him drive it.

The ease and luxury and implausible grandness of Lord Peter’s life certainly contributes to the divided response he provokes. Many people find him ridiculous: too suave, too aristocratic, expert in too many fields (incunabula, cricket, international relations), sentimental and embarrassing when he has scruples (as he always does at the end of the story) about sending the murderer to the gallows.

At the same time, though, he has a gift for speaking the truth to everybody, peer and charlady alike. He never spares himself in pursuit of a criminal, and he has an attractive understanding of the lot and toils of the women of his age. Sayers has Wimsey bankroll an agency, for example, that specializes in sending ‘surplus’ women out to useful work. Run by Miss Climpson (a spinster herself, of course), the employment agency gives its women workers money and purpose, and provides Wimsey with all the adjutants he might need for his cases. Miss Climpson, rather like Miss Marple, is a particularly capable secret agent: in Strong Poison (1930) she insinuates herself into cafés and households − in her unthreatening way − to pick up vital information. She’s even capable of pretending to be a medium, and of tricking a nurse into thinking that the spirits of the dead require her to reveal the hiding place of a vital missing will.

The sympathetic side of Wimsey emerges only slowly as he opens himself up to his mother, and to his faithful ‘man’ Bunter, his former batman from the trenches. He eventually reveals himself to be suffering from survivors’ guilt and what we would call post-traumatic stress disorder from his experiences in the First World War. Beneath the suave exterior, he is a deeply damaged person.

Despite that, one feels that Sayers would have been better off sticking to Lord Peter. In real life, however, she became entangled with John Cournos, a Russian Jew working in London as a journalist. He liked interviewing literary figures, and Sayers described him as the kind of man ‘who spells Art with a capital A’. It was not an easy relationship. ‘It’s such a lonely dreary job having a lover,’ she wrote: ‘One has to rely on him for companionship, because one’s entirely cut off from one’s friends … it’s so dirty to be always telling lies, one just drops seeing them. One can’t be open about it, because it would end by getting round to one’s family somehow.’

Despite that, one feels that Sayers would have been better off sticking to Lord Peter. In real life, however, she became entangled with John Cournos, a Russian Jew working in London as a journalist. He liked interviewing literary figures, and Sayers described him as the kind of man ‘who spells Art with a capital A’. It was not an easy relationship. ‘It’s such a lonely dreary job having a lover,’ she wrote: ‘One has to rely on him for companionship, because one’s entirely cut off from one’s friends … it’s so dirty to be always telling lies, one just drops seeing them. One can’t be open about it, because it would end by getting round to one’s family somehow.’

After a long, slow struggle, Cournos finally talked Sayers into sleeping with him, much against her religious principles. Disaster followed. ‘I dare say I wanted too much,’ she wrote, bitterly, after he had deserted her: ‘I could not be content with less than your love and your children and our happy acknowledgement of each other to the world … you went out of your way to insist you would give me none of them.’

After the split with Cournos, she consoled herself with a very different character. Easy-going, fond of dancing and cars, Bill White was merely a stand-in. She slept with him, too, almost casually this time, and became pregnant. But White was no more cut out for fatherhood than Cournos had been, and Dorothy was left on her own. The first royalties from Whose Body? came in handy for doctors’ bills. She took just eight weeks off from the office and − fearful of telling her parents − travelled to Hampshire to give birth in a private nursing home.

Once her son was born, Dorothy arranged for him to be looked after by a cousin. It seems that no one else suspected what had happened. Flush with funds to spend on food, Dorothy had been putting on weight, which disguised the pregnancy. Her parents would never know their grandchild, because Sayers’ moral standards did not allow her to brazen things out. Above all, Sayers was a principled, conventional member of the Church of England, and this would cause her, for the rest of her life, publically to deny her son.

In fiction, too, P. D. James rightly points out that Dorothy was conventional, ‘an innovator of style and intention not of form’. She stuck to the rules of the Golden Age in her novels: a limited circle of suspects, a frequently implausible method of murder and a neat denouement at the end. The ever more bizarre and complex methods of the killing in Sayers’ novels were in fact part of their attraction. ‘Those were not the days of the swift bash to the skull followed by sixty thousand words of psychological insight,’ James adds. ‘The murder methods she devised are, in fact, over ingenious and at least two are doubtfully practicable. A healthy man is unlike to be killed by noise alone, a lethal injection of air would surely require a suspiciously large hypodermic syringe.’

However, Sayers did move away from convention through the development of the character of Lord Peter Wimsey, and particularly through the relationship he formed with the plucky and vulnerable Harriet Vane.

Vane, Sayers’ fictional alter ego, was another writer of detective stories. Like Sayers, Harriet was independent and bold and yet had been wounded by men. When she first appears in Strong Poison, it is in the dock. In an echo of Sayers’ relationship with Cournos, Harriet had agreed to live, unmarried, with a man. She too paid a high price for it, being accused of his murder.

Harriet’s salvation from the gallows comes in the form of the brainy and wealthy Wimsey, who, while clearing her name, falls in love with her. After a suitably prolonged period of disputations and misunderstandings, Harriet ends up united with him in wedded bliss and material splendour. Sayers’ tragedy was that there was no such happy ending for her.

Gaudy Night is the book in which Harriet finally realises that her lover will never attempt to subdue or stifle her, and that she can relax into this relationship. The sparkling fairy on top of the tree of Sayers’ work, Gaudy Night is a beautiful love story and a serious exploration of whether it was possible, in the 1930s, for women to combine work and marriage. The reader who has accompanied Harriet and Peter through hundreds of pages in which Harriet refuses to surrender her hard-won independence and pride will cheer when they finally kiss, in New College Lane, rather shyly and foolishly speaking to each other in Latin. It’s a heart-warming if exasperating end (what took them so long?) to a very curious love story, in which the head plays as great a part as the heart. Typically of Sayers, she argues that the intellect brings her two lovers together. As she put it in her own words, she had at last found a plot in Gaudy Night that exhibited ‘intellectual integrity as the one great permanent value in an emotionally unstable world’. This was the book in which she found herself saying ‘the things that, in a confused way, I had been wanting to say all my life’.

To hear Gaudy Night written off as the critic Julian Symons does in Bloody Murder (1972) is not unusual, but it remains infuriating. When I read the page where he states that ‘Gaudy Night is essentially a “woman’s novel” full of the most tedious pseudo-serious chat between the characters that goes on for page after page’, I threw Mr Symons’s book on the floor, and stamped upon it.

***

Sayers did eventually get married, to Captain Oswald Fleming, a divorced journalist. James Brabazon, Dorothy’s biographer, who knew her, wasn’t able entirely to pin down the nature of the relationship with her husband:

Conventional comic images of the tiny henpecked husband alternated with more melodramatic versions of the mad monster chained in the attic. Slightly closer to the truth was the theory of the unpresentable alcoholic. But what seemed quite clear was that this was by no means what we in those days regarded as a normal marriage.

Fleming was kept at home in the house Sayers bought in the Essex village of Witham. He was not introduced to her friends, and was apparently unable, through ill health, to earn a living himself. All he seemed to have in common with Lord Peter was his inability to recover from his experiences in the First World War.

As the years went by, Sayers dropped detective fiction, having apparently felt that she had exhausted its possibilities. She wrote increasingly for the radio and the stage, and became a noted translator of The Divine Comedy. Her ever-present Christian beliefs also inspired her to retell Bible stories simply, for a new generation, in the new medium of radio. Their success reinvigorated the faith of many of her fellow churchgoers, and the Church of England was so pleased that she was offered an honorary doctorate in Divinity. But Sayers turned it down, perhaps fearing that her private life would not withstand scrutiny.

It seems possible that, had she continued husbandless, or if she had married a more understanding man, Sayers may have eventually felt able to have her son come to live with her. But it never quite happened. Decades later, she was still using the presence of her Aunt Mabel, a surviving and possibly censorious relative, to argue that the time was still not ripe.

Sayers’ son knew her as ‘cousin Dorothy’, and received regular money and visits, but never any public recognition of their relationship. He eventually discovered the mystery for himself, when he sought out his birth certificate to apply for a passport: it seems that seeing Sayers named as his mother was not a surprise. It seems rather shocking that Sayers, literate to a fault in her work and in public, was so emotionally illiterate that this was the way she felt forced to introduce herself, as a mother, to her child.

But when Sayers threw herself behind a cause − as she often did, having a stable-full of pet hobbyhorses which she liked to exercise − she had a voice and authority that could achieve considerable change. Whether she was exhorting the Church of England to make itself more accessible, or universities to give degrees to women, she would use her heavy guns: rhetoric, passion and humour. Here she is in 1938 answering the question ‘Are Women Human?’

When the pioneers of university training for women demanded that women should be admitted to the universities, the cry went up at once: ‘Why should women want to know about Aristotle?’ The answer is NOT that all women would be the better for knowing about Aristotle … but simply: ‘What women want as a class is irrelevant. I want to know about Aristotle. It is true that many women care nothing about him, and a great many male undergraduates turn pale and faint at the thought of him – but I, eccentric individual that I am, do want to know about Aristotle, and I submit that there is nothing in my shape or bodily functions which need prevent my knowing about him.

In its quicksilver cleverness, its comedy and its belief in the importance of intellect, it is the unmistakable voice of Dorothy L. Sayers.’

That was the chapter called ‘A Life Less Ordinary’ from my book A Very British Murder.

To read more about murder you might like my post on female detectives, or on how to film a murder in a library.

I have to admit that my favourite has to be A Busmans Honeymoon. Having said that, I love all the Lord Peter books.

After reading that I could murder a pint.

I have ordered her first novel after watching your programme! I used to wirk in the library in Witham, it has a room devoted to Dorothy L Sayers, there is an annual lecture, and a nice statue opposite.

Having read all of Sayers crime novels and short stories I have to say that ‘Gaudy Night’ is my least favourite novel. While it may have been important to Sayers but does not fit comfortably within the detection of the crimes in the college. It strikes me a weakness that after having gathered all the evidence Harriet Vane cannot solve the crime but has to present the problem to Wimsey to solve for her.

Ignoring whether old Noakes would stand in the right spot to be hit by the plant pot, the fact that so many clues are ignored such as the fishing line hanging from the pot in the morning are conveniently glossed over.

It is a pity that Sayers crime writing did not follow the path that she suggests that Harriet Vanes was taking. If not that Chief Inspector Parker is a character that could have been developed in his own right or the travelling salesman Montague Egg from the short stories.

I can reread Sayers for pleasure particularly ‘Five Red Herrings’ and the ‘Nine Tailors’ but on the whole my tastes have moved on and I prefer many of the more recent european crime novels. This included one I came across by chance called the ‘Giggolo Murders’ set in Turkey where the detective is a transvestite nightclub owner and performer. It takes all sorts.

I think that the Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club stands comparison with other non murderous fiction as a snapshot of the countery in the immediate aftermath of the First War.

The whole plot line hinges on the fact that at that time and in that place the country would come to a halt to remember the dead.

Equally the portrait of the shell shocked veteran in my opinion stand comparison with the similar character in Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway

Perhaps it is time for the BBC to rerun the Wimsey Mysteries again Both the Ian Carmichael ones and the later Harriet Walter Edward Petherbridge episodes

I am amused at the commenters who disapprove of Gaudy Night because it does not conform to their standards for proper detective novels. I am rereading it for the fourth time with great pleasure, because I care about the protagonists and the way their relationship comes off. The mystery is only the pretext.