A Girl’s Guide to Greatness, or How Not to Write an Obituary

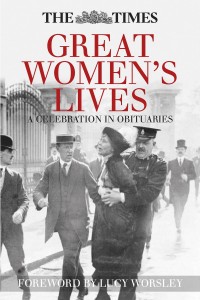

Last summer, as I was reading through the 1,000 or so pages of The Times Great Women’s Lives: A Celebration in Obituaries in preparation for writing its foreword, I was struck by how ridiculous and retrograde it was for so many of the obituaries to concentrate on the women’s hair, cooking skills and home life.

Last summer, as I was reading through the 1,000 or so pages of The Times Great Women’s Lives: A Celebration in Obituaries in preparation for writing its foreword, I was struck by how ridiculous and retrograde it was for so many of the obituaries to concentrate on the women’s hair, cooking skills and home life.

‘HA! At least those days are over,’ I thought to myself.

But then this happened. Unbelievable!

Anyway, it seems timely to give you an extract from my foreword to that book of great women, which has a few pointers for those of us who wish to achieve greatness. And a few pointers too, for how not to write an obituary.

‘What it is makes a woman great? The answer, as revealed in these 124 obituaries from The Times newspaper, has changed over timein ways that can’t fail to fascinate.

One of the encouraging themes of the collection is that scientists, writers, performers, politicians and campaigners are not born, nor are they made. They make themselves. A soaring rise from a humble background certainly makes for a good obituary, and the words ‘she became the highest-paid woman in America’ make a satisfyingly frequent appearance in this collection. We learn that Eva Peron, First Lady of Argentina, was a ‘Cinderella in real life’ to the young people she inspired, and I was tickled to discover that the Labour politician Dame Barbara Castle began her career selling crystallized fruit in a Manchester department store while dressed as ‘Little Nell’. A tragic death cutting off early promise also makes for a striking story: aviator Amy Johnson at thirty-seven in 1941; troubled singer Amy Winehouse at 27 in 2011; mountaineer Alison Hargreaves on K2 at only 33 in 1995.

It might not surprise the cynical to discover how important good looks have been to the greatness of women, or at least, so it has been in the eyes of their obituarists. The suffragette Christabel Pankhurst, we hear, was ‘a most attractive young woman with fresh colouring, delicate features, and a mass of soft brown hair’. Striking looks, constantly mentioned, sometimes had unusual consequences: the blue-eyed Swedish soprano Jenny Lind, for instance, gave her name to a breed of potatoes with blue specks on their skins. The only woman in the whole collection whose looks are disparaged seems to be George Eliot, notable for ‘her resemblance to Savonarola’. With all this emphasis on appearance, I don’t blame Joan Crawford in the slightest for keeping her birthdate so secret that The Times was only able to give her age at death as falling somewhere in the range between 69 and 76.

And being nice has been just as good as being good at what you do. It’s a strain that persists surprisingly, and depressingly, far through the collection’s chronology. Among the earlier subjects, Christina Rossetti produced writing that manifested ‘purity of thought’, while it was the happy lot of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the first female doctor to qualify in England, to ‘emerge not only successful but still a ‘womanly woman’.’ But when you reach obituaries from the late twentieth-century, the convention of the lovely lady persists in ways that read almost like a parody: the crystallographer Dame Kathleen Lonsdale was described in 1971 as looking ‘in no way unfeminine’, despite having ‘golliwog’ hair, and is praised for having ‘made herself a neat hat for a few shillings’ for a visit to Buckingham Palace. ‘The most successful princesses in history’, claims the obituary of Diana, Princess of Wales, in 1997, ‘have been those who loved children and cared for the sick’. Not exactly an uncontestable statement.

Because of the same convention of niceness, the early obituaries sometimes have difficulty in expressing what they’re talking about. Philanthropist Baroness Burdett-Coutts founded a ‘Home’ at Shepherd’s Bush for single mothers, which was euphemistically described as ‘one of the earliest practical attempts to reclaim women who had lost their characters’. It’s actually quite hard to puzzle out exactly what Josephine Butler did, so obliquely is it described in her obituary. She’s hailed as ‘a woman of extreme delicacy and refinement of mind, with a horror … of contact by vice’. In fact she campaigned against the Contagious Diseases Act, which decreed that on the mere so-say of a policeman, a women could have her private parts inspected for venereal disease and be imprisoned if she refused.

If you can’t be nice, however, be difficult. This theme emerges as the decades pass. Here Bette Davis excelled: ‘Nobody’s as good as Bette when she’s bad’, while the French actress Sarah Bernhardt slept in a coffin and killed her pet alligator by giving it too much champagne. And being angry works, too. Coco Chanel, inventor of the strappy sandal and the cardigan jacket, had a come-back in the 1950s inspired by the ‘irritation of seeing Paris fashion taken over by men designers’. Pat Smythe, international showjumper, might have been equally chagrined at being given a silver cigar box for winning a competition with the words: ‘Sorry about this, we were not expecting a woman rider to be as good as you’. Being uncommunicative seems an excellent means of finding the time to get on with being great. Elizabeth David, the cookery writer, instructed directory enquiries not to tell anyone her number, ‘under any circumstances, even in case of death’, while Barbara McClintock, Nobel Prize-winning scientist said that ‘anyone who wanted to talk to her … could write a letter’.

Being on the left politically will definitely help you achieve greatness, because it puts you in the vanguard of struggle and change. We have ‘Red Ellen’, the Labour MP Helen Wilkinson (following the rules about good looks above, she nevertheless had an ‘oddly picturesque person’) and ‘the Red Dame’, actress and CND supporter Peggy Ashcroft. Movingly, the former ‘Little Nell’, Dame Barbara Castle, gets a standing ovation at the Labour Party Conference at the age of 86 even before having reached the microphone.

Most of all, though, it’s courage that’s celebrated here. Courage is what links Emmeline Pankhurst, campaigner for votes for women, who was ‘of the stuff of which martyrs are made’, to Odette Hallowes, who had her toenails pulled out during the war for her Resistance work. She shares it too with Marian Anderson, the first black singer to appear at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Refused tuition at a Philadelphia music school on the grounds that ‘we don’t take coloured’, Anderson reportedly trembled when she first stood on the stage of the Met. In her own words, though, it was worth it: ‘my mission is to leave behind me a kind of impression that will make it easier for those who follow’.

Well, all of these women have done this, wonderfully well, even the ones with messy hair.’

You can buy the book here.

Hi Lucy very topical – last week Australia’s largest newspaper’s obituary of Colleen McCullough, author of The Thorn Birds, described her as ‘plain and overweight’ so there is still a little way to go…

http://www.foxnews.com/world/2015/01/30/australia-newspaper-criticized-over-obituary-for-thorn-birds-author/

“Pat Smythe, international showjumper, might have been equally chagrined at being given a silver cigar box for winning a competition with the words: ‘Sorry about this, we were not expecting a woman rider to be as good as you’. ”

Something similar happened to my sister in elementary school. There was a math contest and she won. First prize was a baseball mitt as they were assuming the winner would be male.

I was horrified at the obituary of Coleen McCullough. What possible reason could they have for criticizing her appearance?

[Note to Self: Ply alligator with champagne only in moderation. Special occasions only, like birthdays and New Year’s.]

Don’t you think that rather than not commenting on women’s personal and physical assets, it will in future become more common for men to be obituitarised in the same way, now that young men are under similar pressures to be attractive in order to be allowed to succeed?

Super stuff…perhaps you can work on the injustices of the inheritances of titles and surname law, always through the male line, only two are through female and you are considered practically the enemy when a female scots marries another clan, she becomes their property….she has to wear their clan and is no longer considered a member of her own clan at birth. These laws are still going strong and no-one is doing anything about it, least of all the monarchy which bends the rules through females whenever it needs to. However if a woman has tonnes of money and mansions to bring to a family, then miraculously the rules are bent again……