It’s publication day for ‘A Very British Murder’ …

… so here’s a recent article, from ‘The Mail on Sunday’, to tell you what it’s all about.

Wearing a demure white mob-cap, I step out onto the stage of London’s Old Vic theatre.

I am Maria Marten, a village maiden, secretly meeting my lover. But my – or Maria’s – happiness is to be short-lived. He raises a pistol, and shoots me in the head. I shriek. The director tells me to die a horrible death with plenty of groaning. I relish every moment, although it is quite hard not to giggle.

I am taking an acting lesson to learn about ‘melodrama’, an over-the-top, flamboyant form of theatre, rather like modern pantomime. And all the best melodramas feature a bloody murder. In the early nineteenth century, violent death was the new obsession that would come to dominate the British entertainment industry.

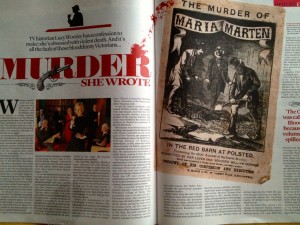

Maria was the heroine of a play called ‘Murder in the Red Barn’. But before that, she was a real person. We would never know her name today but for the fact that in 1827 she was murdered by her lover, and buried under the floor of a Suffolk barn. Lurid plays based on true crimes like Maria’s were staples at the Old Vic. People called it ‘The Blood Tub’ because of the volume of gore spilled there nightly.

It sounds gruesome, but before we condemn our ancestors for their blood lust, we should look to our own pastimes. Our TV schedules are packed with violence: murder, detection and retribution. Computer games are even worse. And we all, to a greater or lesser extent, share this thirst for blood. It’s even present in the sedate pleasure of reading an Agatha Christie.

You might think that the ghoulish interest we take in slaughter is timeless. Researching my new book A Very British Murder,though, I discovered that it dates only from the early years of the nineteenth century.

Before then, people were more worried about famine, plague or war than they were about being murdered.

It was the Industrial Revolution that brought people to live in cities where they didn’t know their neighbours. Alongside gaslight, and drains, and the conveniences of modern life, an insidious new fear threatened society. An unknown murderer, stalking the streets.

The fear really took hold in 1811, the year of the so-called ‘Ratcliffe Highway Murders’ in the crowded docklands of London. A young family of four, mother, father, baby, and apprentice, were slaughtered in their Wapping home, and the case was never satisfactorily solved. In 1810, there had only been fifteen convictions for murder in the whole of Britain. Now four people had all been killed in one night. No wonder East Enders were terrified.

The Ratcliffe Highway Murders were reported all over Britain. Journalists began to make the link between what they called ‘a stunning good murder’ and a spike in newspaper sales. The writer Thomas De Quincey was quick to notice, and to mock. In an epoch-defining essay called ‘On Murder as Considered as One of the Fine Arts’, he said that Britain had become a nation of ‘murder fanciers’. He even imagined a sick new kind of club where ‘connoisseurs of murder’ discuss their favourite crimes.

That’s the background to the melodrama of Maria Marten. Her killing also kick started a new industry of ‘murder souvenirs’. You could buy a ceramic model of the Red Barn for your mantelpiece, or you watch her being murdered all over again at a puppet show. There’s a beautiful Victorian ‘Maria’ marionette at the Victoria and Albert Museum today.

In real life, Maria’s murderer, a cad named William Corder, was caught, tried and hanged. And then his very corpse became another gruesome product of the murder industry. His scalp was exhibited for money, and remains on display in a museum in Bury St Edmunds to this very day.

Melodrama was beloved mainly by working class people, but the fascination with murder ascended up the social scale as the Victorian age progressed.

The sensational crime committed by Dr William Palmer of Rugeley, Staffordshire, in 1855, made the middle classes shudder. Dr Palmer, apparently a respectable doctor, was in fact deep in debt. He administered strychnine in subtle doses, making it look like his victim had died of natural causes.

The Victorians believed that this new sophistication in the ‘art’ of murder was caused by the growing industry of life insurance.

If you took out a policy on your life, you were also unwittingly giving your family a financial motive to bump you off. And poison was particularly scary because it could come by the hand of someone you trusted, like a doctor, housemaid, even a relative.

In 1861, a real-life ‘country house murder mystery’ took place in the Wiltshire village of Rode. The murderess was a sixteen-year-old girl, Constance Kent. She sneaked her three-year-old half-brother out of bed, slit his throat, and hid his body down an outdoor privy.

All this came out years later, when Constance confessed. At the time, the posh mansion, the closed circle of suspects, and the family’s scandals (Constance’s mother had died insane, her father then married the governess) gripped newspaper readers.

Many twists from this case crop up as fiction in some of the most addictively-readable novels ever written, the so-called ‘Sensation Novels’ of the 1860s, which include Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone and Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret.

Both the police and the private detective became more professional as the nineteenth century unfolded, and both made their mark inmagazine stories and novels. Sherlock Holmes first appeared in 1887, just months before the series of brutal slayings in Whitechapel that are chalked up to the unknown serial killer nicknamed ‘Jack the Ripper’. Rather like the Ripper himself, Holmes was powerful and mysterious, as if he were the moral flipside of the most evil killer of his age. Holmes went on solving cases for decades, right into the 1920s. He was even brought back from the dead for commercial reasons after his bored creator, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, had killed him off.

But the Great War caused a sea change in detective fiction. Holmes often physically grappled with suspects and was handy with a gun. After four long years of fighting, readers had had enough violence. Enter Hercule Poirot, who prized brains over brawn, and of whom it was said ‘the neatness of his attire was almost incredible; I believe a speck of dust would have caused him more pain than a bullet wound’.

Hercule Poirot and the other rather sedentary sleuths of the 1920s and 30s such as Lord Peter Wimsey were created by a new generation of female crime authors.

Agatha Christie, Margery Allingham and – my own favourite – Dorothy L. Sayers, produced novels a bit like knitting: detailed, wonderfully plotted, full of social observation. The actual moment of murder was very rarely described. These writers wanted to soothe and entertain, not provoke strong feelings.

This was the ‘Golden Age’ of detective fiction, when British authors churned out case after case set in vicarages or seaside hotels.

This was the ‘Golden Age’ of detective fiction, when British authors churned out case after case set in vicarages or seaside hotels. But eventually their narrow and rather snobbish world would seem a little stale. There was no sign here of the Great Depression or the rise of Fascism, just another body in another library.

But across the Atlantic, a chilling new type of crime writing was catching on. The so-called ‘hard-boiled’ detective stories of American writers like Raymond Chandler would influence British novelists such as Graham Greene. By the late 1930s, the thriller had been born. Amoral, violent and brutal, this American influence represented the future of British crime fiction. The stage was set for the post-War entrance ofJames Bond, the glamorous but psychopathic spy. And it is the thriller, rather than the sedate and cerebral ‘Golden Age’ detective story, which dominates crime fiction to this day.

Hi Lucy, loved all your TV series and looking forward to your Very British Murder series later this month. It’s wonderful to see and listen to someone present a program with such ease, naturalness, and with a sense of humour like you have. I’d love to have come to one of your September talks, but couldn’t get to any of the places you’re going to. Maybe you could include Manchester in future.

Jo.

Hi Lucy,

I’ve just finished your book ”Courtiers” about royal circles in the 18th century. I really enjoyed it and found it enlightening. I hadn’t realised how interesting Queen Caroline (George II’s wife) was.

Fascinating stuff!

I look forward to your take on “A Very British Murder”.

Like you, my favourite crime author is Dorothy L Sayers – particularly “Gaudy Night” which I’ve read time and time again.

Best wishes

Patricia

Welcome back.

This brings back memories of “Mrs White,in the Conservatory,with a candlestick”….

While the genre is somewhat dominated by the hard boiled approach of authors like Fleming and others ;there is still a following for the classic English dectective story One of the best of the modern authors who use this format is Colin Dexter whose books exhibit the minimum of violence.. Baroness James I think is carrying on the great tradition of D LSayers with her Dalgliesh novels which have well rounded believable characters whose actions remain consistant from book to book Such is the following for this kind of novel that my local Waterstones had a section labelled cosy crime!

Have copy of new book looks fantastic

Enjoyed episode 1 of the TV series on murder. In it was suggested that there was an increase in the murder rate around the end of the 18th century. I would imagine that murder would never have been an unreported crime, so what would the reason(s) be for such an increase?

Oooh, can’t wait to get my hands on this one. And a TV series too? With any luck, TVOntario will treat us to it next year.