Why I like Victorian murderesses

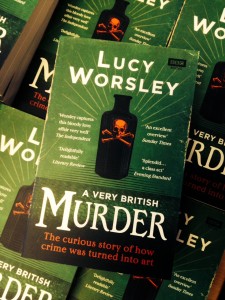

This week, I’m happy to say, my book about the history of detective fiction is out in paperback. A bargain, if I may say so myself, at £9.99 (or even less from the Evil Empire). To get you in the mood, I’m posting an extract from one of my favourite chapters, which is about Victorian murderesses…

This week, I’m happy to say, my book about the history of detective fiction is out in paperback. A bargain, if I may say so myself, at £9.99 (or even less from the Evil Empire). To get you in the mood, I’m posting an extract from one of my favourite chapters, which is about Victorian murderesses…

‘The men of the middle classes do not choose that their females should work for money, so we have no option but … the monotonous round of home-pursuits − busy idleness, unremunerative employment.’

Anonymous female writer in The National Magazine, 1857

As we’ve seen in the case of Maria Manning, the Victorians found it hard to know what to think about murderesses. The female members of middle-class families were supposed to be pure, virtuous, most influential within, and best confined to, the domestic realm. What was a murderous woman, then? She must be crazed, wanton, or suffering from some horrible sickness. This was necessary to protect her father, husband and male associates from accusations that they had failed to keep her in check. It was impossible that she could look or behave like a normal person.

And if she did look and behave normally, what then? Despite the difficulties that lie in revisiting and attempting to resolve cases more than a century old, it seems perfectly possible that a couple of the celebrated poison cases of the later nineteenth century involved women who actually managed to get away with their crimes. This was in part because, despite the considerable evidence against them, people simply couldn’t quite believe that a well-born, well-spoken, attractive young female could have committed murder.

***

In 1857, when she was only 22, a young lady named Madeleine Smith was accused of poisoning Pierre Émile L’Angelier a young man from a lower social class. Brought up in upper-middle-class Glasgow, cosseted by her parents, Madeleine began her relationship with L’Angelier when she was 19 and recently returned home from boarding school. Conventionally for her background and station, Madeleine’s education had been devoted to preparing her for life as a wife. This was, in many ways, a training in the art of deception. In many boarding schools, the mistresses read all the pupils’ correspondence, with the result that the girls would bribe servants to deliver private letters. ‘Concealment and deception prevail in girls’ schools,’ ranted Fraser’s Magazine. ‘Girls learn to grasp after show and pomp; and, as women can rarely acquire these for themselves, they are taught to look at marriage as the means of making their fortune.’ It was true too of life beyond the schoolroom: Madeleine’s success or failure would be measured by the speed and splendour of her engagement.

In 1857, when she was only 22, a young lady named Madeleine Smith was accused of poisoning Pierre Émile L’Angelier a young man from a lower social class. Brought up in upper-middle-class Glasgow, cosseted by her parents, Madeleine began her relationship with L’Angelier when she was 19 and recently returned home from boarding school. Conventionally for her background and station, Madeleine’s education had been devoted to preparing her for life as a wife. This was, in many ways, a training in the art of deception. In many boarding schools, the mistresses read all the pupils’ correspondence, with the result that the girls would bribe servants to deliver private letters. ‘Concealment and deception prevail in girls’ schools,’ ranted Fraser’s Magazine. ‘Girls learn to grasp after show and pomp; and, as women can rarely acquire these for themselves, they are taught to look at marriage as the means of making their fortune.’ It was true too of life beyond the schoolroom: Madeleine’s success or failure would be measured by the speed and splendour of her engagement.

Despite his romantic name, L’Angelier was far from being the rich, dream husband Madeleine’s parents desired. Originally from Jersey, he had had spent some time in France, and was now a clerk in a shipping firm. His friends in Glasgow described him as being moody and dissatisfied with his lot. He met Madeleine in the only possible place where such an intersection of the classes could happen: out on the public street. Attraction sparked between them immediately, and they went on to exchange over sixty letters, which were smuggled out of Madeleine’s parents’ house by a maidservant. Madeleine showed herself to be pragmatic to the point of cold-heartedness in arranging all this. She blackmailed a family servant into delivering the letters, by threatening to reveal that this maid had an unauthorised young man of her own.

Madeleine and L’Angelier (they called each other ‘Mimi’ and Émile’) also had secret meetings during which their physical relationship progressed beyond the point – for a Victorian young lady – of no return. She took issue with the very real expectation that she should marry well. ‘It was expected that I would marry a man with money,’ she wrote to Émile, but ‘I take the man I love. I know that all my friends shall forsake me, but for that I don’t care.’

When Madeleine’s side of this correspondence emerged during the course of her trial, it caused a sensation. It showed that even a middle-class girl could want, indeed enjoy, sex. ‘I am now a wife, a wife in every sense of the word,’ she wrote to Émile on 27 June 1856, although they had not of course actually undergone a wedding ceremony. ‘I can never be the wife of another after our intimacy,’ she promised, reassuring herself that: ‘Our intimacy has not been criminal, as I am [his] wife before God, so it has been no sin our loving each other.’

However, Émile never married his Mimi. Over time she cooled towards him – something else that young ladies were not supposed to do – and tried to fob him off with various excuses. Her parents, unaware of their daughter’s relationship, were putting pressure on her to marry, and she feared they might discover everything. Finally, Émile learned from a third party that Madeleine’s parents had arranged for her to marry someone else who was much more suitable, one of her father’s business associates.

It seems that Madeleine feared that her cast-off lover, hurt and angry, had the power to ruin her life by revealing all about their relationship. She certainly begged him not to, writing: ‘Émile, for God’s sake, do not send my letters to papa. It will be an open rupture. I will leave the house. I will die …’

In March 1857, they had several more assignations − tearful and tortured, one imagines − Madeleine inside her parents’ house and talking to Émile through the kitchen window. At one of them she gave him a cup of hot chocolate; afterwards he suffered from an upset stomach. Two days after their final meeting, he died.

It was the discovery of Madeleine’s letters at Émile’s lodging house that drew her to the attention of the police. They also found her name in a chemist’s ‘Poison Book’, which revealed that she had made two recent purchases of arsenic. The poison could have been intended, as Madeleine claimed, to kill rats, or else as a facial treatment. But it could also have been a way of ridding herself of a grave, and potentially life-wrecking, embarrassment.

Madeleine’s letters themselves were not read out during her trial, and now we see how a descending veil of decency began to obscure the true details of her actions: ‘All objectionable expressions, all gross and indelicate allusions were carefully and studiously omitted … that the feelings of the prisoner might not be overwhelmed by such a terrible publicity.’

And, despite the damage to her reputation, Madeleine Smith got off. She was a young, attractive, romantic figure, and aroused a great deal of sympathy. She simply didn’t look like a murderess. Reports of her behaviour in prison made her sound well brought up and innocent: she spent her time ‘in light reading, with occasional regrets at the want of a piano’. Even the phrenologist appointed to ‘read’ Madeleine’s character from the shape of her skull found her admirable, with a propensity for mathematics. ‘Owning to her strong affections and healthy temperament,’ he wrote, ‘she will make a treasure of a wife to a worthy husband.’ This was a sharp contrast to the conclusions reached on William Palmer. One suspects that these phrenologists tended to be influenced by the impression they had formed of the person before even feeling his or her head.

The Scottish jury voted the accusations against her ‘not proven’, the announcement was cheered in court and the world at large glowed with compassion for Madeleine. Among women, she became ‘quite a heroine’. The Northern British Mail claimed that her fellow females regarded her as:

a thoughtless but most interesting and warm-hearted young woman – one who in the simplicity of her heart, in her first love affair, abandoned herself to the man of her choice, with an amount of confiding love and outspoken artlessness of purpose, which, censure or regret as they may, they cannot regard without sympathy and admiration.

To many, it was all Émile’s fault, for seducing her.

The tradesmen of Glasgow even raised a subscription so that the now-glamorous Madeleine would have some money upon which to live. Newspapers bandied around the figure of £10,000. This was raised for the intriguing young girl who may or may not have killed Émile (the verdict of ‘not proven’ was quite as good as ‘not guilty’). Meanwhile, as Judith Flanders points out, Émile’s poor old mother, whose son was dead and who had been left with absolutely no means of support, was also given a gift by the public. She received just over £89.

It’s tempting to see Madeleine’s rebelliousness, her increasingly dangerous choices, as being motivated by boredom with a restrictive, unexciting, middle-class domestic life. The idea that nineteenth-century life was split into separate spheres of influence, public and private, male and female, the powerful and the powerless, can easily be created with choice quotations from advice and etiquette manuals.

But in reality it disguised a more complicated picture. The Victorians defined ‘work’ as an activity that took place outside the home. Therefore, much of what Victorian women did in running houses and contributing to family businesses seemed invisible to the eyes of outsiders. Indeed, to appease the pride of their husbands, many women pretended to work less than they really did.

Even if it was often ignored, though, there was a powerful image in contemporary culture of the ideal female as calming, decorative, exerting a moral influence through virtue, rather than an active influence through the toil of her hands or brain. Madeleine Smith seemed unenthusiastic, or at least ambivalent, about this vision of her future – but it was an ideal that eventually saved her.

This story of a young girl hiding from the consequences of her crime behind the conventional view of Victorian womanhood seems almost too good to true, bringing out as it does all the clichés about nineteenth-century society. Historians of the period are at pains to point out that the supposed neuroses and anxieties about the body that make up such a significant part of our popular idea of Victorian middle-class life are merely a twentieth-century construct. For example, the celebrated myth that the Victorians thought piano legs immodest and covered them up in special fabric sleeves has long been exploded. Of course not every Victorian female teenager was virginal, nor was every married woman in comfortable circumstances kept happy and busy by domestic duties, church attendance and bringing up her children. Yet neither were they all seething with repression and passions unfulfilled. We still remember women like Maria Manning and Madeleine Smith because they made contemporaries ask questions of themselves about what was womanly, and what was not.’

An extract from Lucy Worsley, A Very British Murder (BBC Books, 2013). To read more about murder click here.

It is interesting to note that both Madeline Smith and Constamnce Kent lived to a very great age in Constance’s case over 100 She became a nurse in AuStralia while Smith was part of the Arts and Crafts Movement before splitting from (but not divorcing) her husband and emigrating to the USA.

Lucy Ithought the book was an excellent read At last someone is sticking up for D L Sayer!

What is it with violence and murder? Every other programme on television these days seems to involve guns, death, bodily harm or criminal activity of some sort or another.

You have many fine qualities Lucy, but you should move on beyone this gruesome one

Hi Lucy,

Fascinating! It just goes to show that human nature never changes, despite temporary social mores!

When you were researching the book, did you look into the Maybrick case? That was another case of “why would you want arsenic anyway?” Particularly strange in the light of the fact that hubby may have been addicted and possibly (?) Jack the Ripper.

Andrew

I want to read this so bad! Any idea when it will be available in the US?

I love Pepys and read him daily on his website, (yes he still sends ’em). Wanted to see his library at Magdelen and found you can book rooms B&B in the colleges. Stayed for 4 days in Trinity Hall, my room was 300 years old. Go every year stayed at Christs, Corpus Christies and Sydney Sussex this year. To breakfast in the old dining halls and learn the history and culture of each college is great. Sure you know the ‘feel’ you get, especially when you have lived and work in those places, from history. Hope this doesn’t sound wierd.

“The Victorians defined ‘work’ as an activity that took place outside the home.”

Isn’t this largely still the case? That if you don’t have a job you don’t work, even if you are raising a family? The pendulum has swung from the 1950s (or Victorian) ideal of stay-at-home wives, to all women being now expected to go out to work, and them being labelled feckless scroungers if they don’t.

Not the point of your piece, I know, but I felt it had to be said.

I loved your TV series – all of them! – and I look forward to the next one.