Why I love Sherlock Holmes

On tonight’s ‘A Very British Murder’, we cover a bit of Sherlock Holmes, so here’s my recent article from the Telegraph about how much I love him. Apologies if you’ve read it already, I did tweet the link on New Year’s Day when it came out. (Oh, and did you know there’s a book to read too?) (Oh yes, there is!) (That’s enough about the wretched book – Ed.)

On tonight’s ‘A Very British Murder’, we cover a bit of Sherlock Holmes, so here’s my recent article from the Telegraph about how much I love him. Apologies if you’ve read it already, I did tweet the link on New Year’s Day when it came out. (Oh, and did you know there’s a book to read too?) (Oh yes, there is!) (That’s enough about the wretched book – Ed.)

So – why do I love Sherlock Holmes?

‘In the East End of London, 1888, a serial killer was on the loose.

A series of slayings of women in Whitechapel had become associated in people’s minds with an imagined single murderer known as ‘Jack the Ripper’. Journalists were delighted to write about a new kind of criminal: mysterious, motiveless, all-powerful. And readers were equally ready for a new type of detective, with powers of his own to equal the ‘Ripper’s’. The stage was set for Sherlock Holmes.

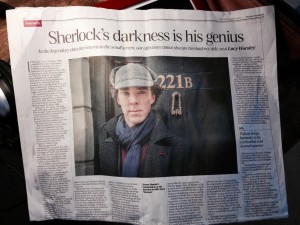

He made his first appearance in Arthur Conan Doyle’s story A Study in Scarlet, published in a Christmas album in 1887. It was re-issued in novel form in the very year of the Whitechapel murders, 1888. Holmes is, of course, still alive and well today, and returns to BBC One on New Year’s Day in his latest incarnation, which is a fantastically clever updating of one of fiction’s greatest characters.

But the historical context is that ‘Jack’ and Sherlock represent two sides of the same coin. The ‘Ripper’s’ crimes had not yet taken place at Holmes’s debut, yet as his character developed during the numerous stories that followed, Holmes became almost the ‘Ripper’s’ mirror image. Both are potent and unmanageable, one good, the other evil. And in a strange intertwining of our images of ‘Jack’ and Sherlock, one of the very few eyewitnesses thought to have actually seen the serial killer reported that he was wearing a deerstalker hat.

It is to Holmes that government ministers, successful businessmen and the royal families of Europe turn for the solution of their knottiest problems. On the whole, though, Holmes’s clients aren’t the great and the good. They also include vicars, typists, engineers, landladies … the very sort of people who had to walk home along the streets at night, who read Conan Doyle’s stories in magazines and who were encouraged by them to imagine that ‘Jack the Ripper’ might yet be caught.

There is something deeply reassuring about Holmes’s uncanny abilities. At the same time, though − exactly in common with people’s conception of the ‘Ripper’ − Holmes is a misfit. Lacking close family ties, subject to deep depression, dangerously dependent on drugs, he is so unfailingly devoted to justice that he acts thoughtlessly or even dangerously. The very first time we see Holmes, in ‘A Study in Scarlet’, he is indulging in a suitably ‘Ripper’-ish activity: beating a corpse with a stick.

But this was because Sherlock Holmes is one of the very first fictional forensic scientists.

Sherlock’s love of science and technology is an important theme of the BBC series, which is absolutely true to the original. In his very first appearance in print, Dr John Watson hears that a friend of friend who works at a hospital is looking for a lodger. Dr Watson himself wants a room, so is keen to meet the unknown chemist.

Dr Watson visits St Bartholomew’s Hospital, where the as-yet-unknown Sherlock Holmes spends much of his time. The mutual friend has warned Watson that Holmes is a crank, ‘a little queer in his ideas’. He has been seen, for example, pounding a human corpse in an effort to establish how far bruises may be created post-mortem.

Holmes is revealed to us in his laboratory, researching toxicology and inventing a new chemical test for the identification of blood. He shakes John Watson’s hand, and greets him with the words: “You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive”.

Dr Watson is astounded by this, and only some time later, after an appropriate build-up of suspense, do we learn that Holmes has ‘read’ Watson’s military bearing, his tanned skin, his haggard face, and his injured arm as evidence that Watson has been in the British Army’s most notorious recent war zone. (The ex-army John Watson in his latest BBC incarnation has also been fighting in what sometimes seems like the very same war.)

In the very first few pages, then, of Holmes’s life in print, we’re introduced not only to the detective himself but to the business of applying science and the technique of deduction to detection.

Arthur Conan Doyle was himself trained as a doctor, and it was one of his own teachers, Dr Bell, whose methods inspired Holmes’s. Doyle described Bell as coming from ‘a very severe and critical medical school of thought’, and possessing ‘remarkable powers of observation. He prided himself that when he looked at a patient he could tell not only their disease but very often their occupation and place of residence’.

Conan Doyle’s genius was to combine Bell’s scientific approach with his own love of storytelling. His original plan had been to settle down happily into general practice as a doctor. Waiting in his surgery for the patients who failed to arrive, he started writing stories in all sorts of genres – horror, mystery, ghost – and sent them off to magazines. But he struck gold only when he decided to try a story ‘where the hero would treat crime in the way Dr Bell treated disease – and where science would take the place of chess’.

Through Sherlock Holmes, Conan Doyle would do a great deal for the popularization and professionalization of forensic science, so much so that the great French forsensic scientist Alexandre Lacassagne, who set up one of the very first police laboratories, would command his new recruits to read the great detective. ‘Fascinating technique’ was his verdict.

But the most gripping thing about Holmes’s character – both in his original and his current forms – is not so much his strength as his weakness.

Many analysts of the detective story format find that the secret of Holmes’s attraction actually lies in his friendship and interaction with Watson. As is the case with Frodo Baggins and Samwise Gamgee, or Morse and Lewis, or Cagney and Lacey, the ‘Watson’ of the pair offers not intellectual, but emotional intelligence. Watsons bring warmth and humanity to their cerebral but cold-hearted superiors.

In one of the later Holmes stories, ‘The Adventure of the Devil’s Foot’, a near-perfect paradigm of the form published in the collection His Last Bow (1917), we see both Watson’s warmth and Holmes’s coolness: it is the combination of the two that’s irresistible. In one immensely tender scene, the two friends stagger out of a room that Holmes has, in the interests of research, filled with poison gas. Sherlock Holmes may appear at first glance to be indomitable, but without his more human friend he cannot navigate life:

I dashed from my chair, threw my arms around Holmes, and together we lurched through the door …

‘Upon my word, Watson!’ said Holmes at last with an unsteady voice, ‘I owe you both my thanks and an apology. It was an unjustifiable experiment even for one’s self, and doubly so for a friend. I am really very sorry.’

‘You know,’ I answered with some emotion, for I had never seen so much of Holmes’s heart before, ‘that it is my greatest joy and privilege to help you.’

Coming as it does toward the end of their lengthy friendship, truths long unspoken are at last expressed. This – not the brains, or the machine-like brilliance – is exactly why I love Sherlock Holmes.

Lucy Worsley’s A Very British Murder is published by BBC Books (£20).’