Poor Queen Caroline and her horrible death…

This week on The First Georgians (Thursday, 9pm, BBC Four) we are covering the life and the horrible death of the wonderful queen Caroline. So here’s an extract from my book Courtiers. It’s part of the chapter about Caroline’s death, which was absolutely my favourite to write. You can also see a video of me reading it here. (Looks like it’s going to be in German, but isn’t.)

This week on The First Georgians (Thursday, 9pm, BBC Four) we are covering the life and the horrible death of the wonderful queen Caroline. So here’s an extract from my book Courtiers. It’s part of the chapter about Caroline’s death, which was absolutely my favourite to write. You can also see a video of me reading it here. (Looks like it’s going to be in German, but isn’t.)

‘When Caroline’s illness was at last successfully diagnosed in November 1737, her doctors made a terrible mistake.

A ‘mortified’ or decayed part of her bowel was now poking out through the wall of her stomach. The Royal Society had recently approved the surgeon Mr Stuart’s book entitled New Discoveries and Improvements in the most considerable Branches of Anatomy and Surgery, which included ‘ruptures of all kinds cured without cutting’. The doctors should really have pushed the bowel back inside and sewn up the hole.

Her late father-in-law had been accustomed to call Caroline ‘cette diablesse la Princesse’ [that devil-woman the Princess], a description which hints at the steely soul hidden inside her plump exterior. And Caroline’s tenacity, resignation and resolution during the terrible days that followed were spectacular.

She now underwent almost daily surgery in her bedchamber, under the knife of Dr John Ranby and his assistant, without the benefit of opium. The energetic Dr Ranby sometimes had to change his cap and waistcoat half-way through an

operation because he’d soaked them in sweat. Peter Wentworth reported that Caroline bravely cracked jokes before he began work each day. ‘Before you begin let me have a full view of your comical face’, she would say to Dr Ranby, and while his blade went in, she’d ask: ‘what wou’d you give now that you was cutting your wife’?

operation because he’d soaked them in sweat. Peter Wentworth reported that Caroline bravely cracked jokes before he began work each day. ‘Before you begin let me have a full view of your comical face’, she would say to Dr Ranby, and while his blade went in, she’d ask: ‘what wou’d you give now that you was cutting your wife’?

Dr Ranby, the son of an inn-keeper, had been a member of the Royal Society since 1724. As a surgeon, he was lower in status than a general physician, but he had perhaps more practical skills. Surgeons trained on the job for seven years, rather than attending university and winning a degree as did the socially-superior branch of the medical profession. They were supposed to restrict themselves to ‘internal’ medicine only, but had branched out into treating sexually transmitted diseases as well. Their activities were closely linked to those of the barber, and regulated by the Company of Barber-Surgeons. Surgeons usually plied their trade in shops and backrooms, working as quickly as they could on patients lashed down and often anaesthetised only with alcohol.

Physicians, on the other hand, jealously guarded their right to make expensive house visits. Poorer people had to make do instead with the advice of the apothecary in his shop full of herbal cures and the traditional symbolic stuffed alligator.

Caroline teased Dr Ranby about his wife, ‘cross old’ Jane, because in November 1737 he was seeking from her not only ‘a separation, but a divorce’. Ranby’s only son was illegitimate, but his irregular personal life had proved no obstacle to his becoming sergeant-surgeon to the Royal Family.

Despite an aggressive and abrasive manner, Dr Ranby enjoyed considerable professional status. He’d published accounts of the medical oddities he had seen during post-mortems such as a bladder containing 60 stones, a boy with an outsize spleen weighing two pounds, and a man whose swollen testicle contained four ounces of water. Tradition has it that Dr Ranby was the inspiration for the uppity surgeon in Henry Fielding’s novel Tom Jones, a character who ‘was a little of a coxcomb’ but ‘nevertheless very much of a surgeon’.

For his operation upon Caroline, Ranby had requested the aid of a comrade. Wise old Dr Bussier, formerly George I’s doctor and now ‘near the age of ninety’, stood near to Dr Ranby to direct him in ‘how to proceed in cutting Her Majesty’. Unfortunately this Dr Bussier ‘happened by the candle in his hand to set fire to his wig, at which the Queen bid Ranby stop awhile for he must let her laugh’. The three of them proceeded with the bleak, black humour of medical students.

The incision into the infected area of Caroline’s stomach had dramatic results. Given an outlet at last, the wound ‘cast forth so great a quantity of corruption’ that it created a horrific stench throughout the room. The doctors still did not quite understand what was going on: they thought that Caroline’s stomach contained an abscess that would grow unless removed.

So they cut away at Caroline’s bowel. If the intestine had been pushed back inside and the rupture sealed up, all may have been well. Cutting the bowel, though, destroyed Caroline’s digestive system, and with it all hope of her recovery.

Even at the time her treatment was recognised to have been flawed. She’d been attended, people said, by ‘a throng of the killing profession trying their utmost skill to prolong her life in adding more torment to it’. She would not be the first, nor the last, person in eighteenth-century London to have ‘died of the doctor’.

The doctors had an arsenal of mass-produced medicines from which to choose drugs to ease Caroline’s pain, including Dr Ward’s Pills, Sir Walter Raleigh’s Cordial, Daffy’s Elixir and its many rivals. (‘Mrs Daffy is pleased to call my Elixir spurious, and insinuates as if it were hazardous to the lives of men’.) Caroline was also offered snakeroot and brandy, usquebaugh (Irish whiskey) and mint-water. Of all of these, mint-water was the only sensible treatment for a digestive complaint, and is still administered in cases of colic today.

But Caroline could not keep these palliatives down long enough for them to take effect, and suffered on stoically without them. In the middle of his undoubted concern for his wife, George II could still be brusque with her, asking why she bothered to eat the food that she vomited up again, and irrelevantly demanding that ‘his last new ruffles’ be ‘sewed upon the shirt he was to put on that day at his public dressing’. Even in this great crisis, George II remained something of his pettifogging self.’

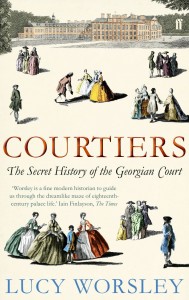

From Courtiers by Lucy Worsley (Faber & Faber, 2011).

What a terrible sad end to a clearly enlightened and interesting woman? I wonder what the rest of George II reign would have been like if she’d lived and what else she might have helped to develop and promote. This is an era of our British history I, unfortunately, know very little about and I have been thoroughly enjoying watching your new series. I will be intrigued to find out more about the Georgians!

As an American, I believe that my history begins with English (and, later, British) history. My ancestors were also originally from England & Scotland, so it is a matter of both national history as well as personal history that interests me.

Are there are good programs that will cover the Regency itself? Not necessarily the Era in terms of describing society – the arts, society as a whole, that sort of thing – but the actual Regency and those involved? I was hoping the Georgians program you have airing currently would cover that, but it looks like it stops before George IV. The whole idea fascinates me, and I’d love to learn more! Are there any documentaries you could recommend (all I’ve found are strictly focused on society rather than the Regency itself & the royals involved) or any in the works?

LOVE your programs! If this Georgians docu-series was ever put on DVD, or the Fit to Rule series, I’d buy them in a heartbeat! I’ve purchased a region-free DVD player so that I can enjoy all the European royal DVDs that haven’t been converted for North America viewers, and probably have more European royal DVDs than American ones! 😛

I suspect that poorer people were in some ways better off than the Queen was. She should have consulted Dr Fothergill (who also treated the poor for free).

I am a bit concerned, Lucy, that this was your favourite chapter, and that in the adjacent picture of you youn were grinning!!

“The Royal Society had recently approved the surgeon Mr Stuart’s book”

Conspiracy Theory: I note Mr. Stuart’s choice of French spelling for his surname. A relative of the prevously regime assasinating the Hanoverian usurper by proxy quackery?

From High tea at Hampton Court to the passing of Queen Caroline, none but the wonderfully lovely and knowledgeable Lucy Worsely can present these stories.

However, down here in the antipodes, we are once again deprived in what we can view on the television.

Although I can watch an occasional Antiques Roadshow, nothing of what you present is available. So please, have a chat with those who run BBC four and tell them about Australia and Australian viewers.

Cheers,

Peter.